Over the years, Sarah Pollman has volunteered in many capacities for the PRC, among them as a gallery sitter, bartender, and ticket-seller. You can see her work and other information at sarahpollman.com.

Sometimes Sarah chases ideas; other times, ideas chase Sarah.

That’s the combination that serendipitously flowed from a cemetery, to a blog, to a small publisher in Sweden, and ultimately to the publication of her book, The Distances Between Us (Trema Förlag, 2016).

She was working on her series Love Notes, which combines tribute photographs that she took and notes she wrote to five artists who inspired her. A small gravestone in a local garden cemetery that she had photographed earlier fit her Sophie Calle piece. The original shot wasn’t good enough, so Sarah revisited the cemetery to get the photograph she wanted.

“I was still in graduate school then,” she says. “Over the course of about week, I raced to the cemetery after class to look for the grave because I didn’t remember exactly where it is. It was November, so the days were really short and the sun was setting every time I was there. At one point, I noticed this Father and Mother stone. So I took a photograph of it, because…why not?”

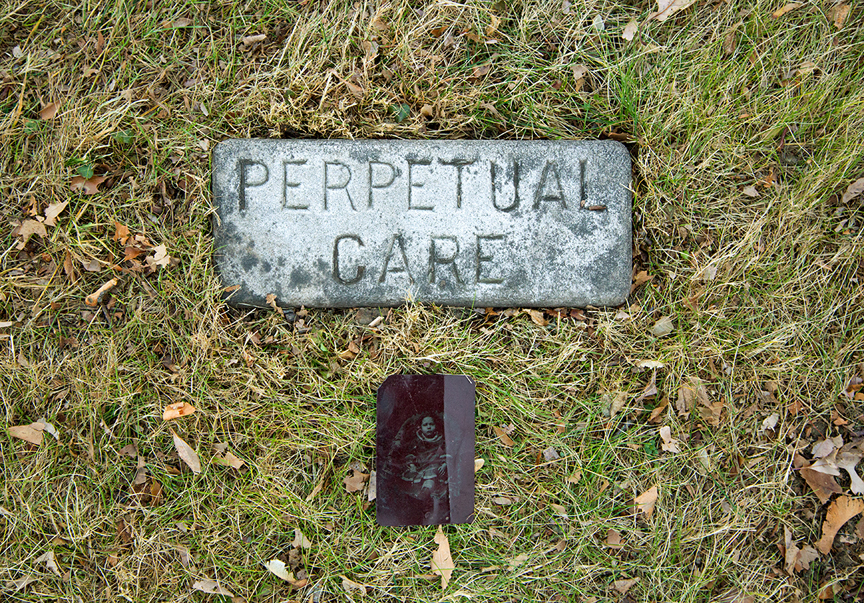

That photograph led to the Father and Mother series of grave markers in New England cemeteries. A starkly different thought struck her while working on Father and Mother. Garden cemeteries are built as parks with beautiful pathways, landscaping and views. But in addition to the more elegant memorials, they often include a counterpoint.

“If you look, you can usually find the section of them that’s the potters’ field. I noticed the insane difference between the haves and the have-nots. It spiraled from there into thinking about, ‘What is the opposite of these high-end cemeteries?’ It’s people who didn’t even get a chance to choose where they were buried because they were buried by the state.”

That’s how her Anonymous Markers series came about. It documents the dispersonal markers of people buried in the unheralded cemeteries of former state-run hospitals, jails and schools.

“Finding those markers was surprisingly difficult. Most of the institutions who had those cemeteries were active only through the 1970s. They didn’t like to advertise that they had them, so most of the cemeteries were offsite, literally in the woods.”

Research could get her close to the locations, but didn’t indicate exactly where they might be. So, she said, finding the cemeteries was a matter of “mostly just traipsing through the woods, following paths and hoping for the best.”

During a lull in the work, Sarah redirected some energy.

“Sometimes when I have nothing going on in my art, I think, ‘Oh, I need to do something.’ So I look for blogs to submit work to. It’s super-low impact [in terms of effort] and it’s a great way to have your work seen.

“I got featured on a blog, and awhile later, got an email that I thought was a scam because it sounded too good to be true. It was Dennis Hankvist from this little, independent publisher, Trema Förlag in Sweden, who wanted to make a book of my work. He really liked the Fathers and Mothers series. Anonymous Markers was still in progress at that time, and after we had some conversations, we decided to include that as well.

“I don’t think my book experience was a very typical one—for example, it didn’t require me to put something together ahead of time. Still, it took close to two years for the whole process to happen.”

Sarah’s currently working on a series of lumen prints that is a perfect marriage between idea and medium. Her lumens are made by using days-long sunlight exposure to contact-print B&W photographic paper. The result is a highly saturated pink monochrome.

“The incredible bubble-gum pink that they turn has me thinking about it in terms of my own history—growing up, being a young girl, and all of the societal ideas of femininity and how a young girl should act and what she wears…

“So I’m exploring objects that relate in some way to memories and assumptions of color and femininity. Photographing a pomegranate, for example, because that’s kind of a historical symbol of fertility, and it’s very pink. At first glance, the monochrome image reads as correct, even though it’s not. So there’s that kind of back and forth for a moment of like, ‘Wait, is that right?’ Another is a red onion, because I’m thinking about layers, or an egg that’s been cracked, but it’s not all the way broken.

“The working title is An Uncertain Past. It’s still in its early stages, and I don’t have all of my ideas fleshed out.”

How would you describe yourself as a photographer?

I work in and around photography. I am committed to the exploration of photographic imagery, its meanings, and its uses, but my projects are not always straight photographs. For example, my project Photographs Purchased on eBay takes a collection of vernacular snapshots that I purchased on eBay as a starting point. I recreated fifty of them in oil paint on panel, and then made a video where I dip the original photographs in bleach, so the viewer watches the original images disappear completely.

What is the primary focus of your photographic work?

It’s the intersection between art and art history. Like the objects in encyclopedic art museums that I love so dearly, photographs are part of the fabric of material culture and carry stories within them: of their own material lives and of the lives of the people who made, collected, distributed and looked at them. I am forever fascinated by the ways in which we all use photography: note-taking, memory-making, legal documentation, personal expression, social interchange and communication. My research and projects take shape around these ideas.

Whose work inspires you?

I’ve had an art-crush on Sophie Calle for years and years. Lorna Simpson, too, and other great artists who use text and image together, such as Andrea Fraser and Carrie Mae Weems. There are just so many amazing artists that it is impossible to name them all, and every artist I encounter gives me a new experience of looking, feeling, experiencing and knowing about the world.

Do you have a mentor or a muse?

My current muses are art museums. I work in the Education Department at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston and really value the time that I spend in the galleries with the objects on view. The objects live and breathe in person in a way that their reproductions in art history texts do not, and these close encounters have greatly influenced my thinking about art history and artistic practice.

I am also incredibly lucky to have a group of smart and driven friends, whose ideas and focus form a rich tapestry of support around me.

What was the Aha moment that sparked your interest in photography?

I have always used photographic ideas in my work, but wasn’t always aware that the photographic underlaid my images. When I was young, I was convinced that I was going to be a painter, but in my first semester of undergraduate studies, I took an introductory photo class with Youngsuk Suh. Eventually, begrudgingly, I admitted that my photography work was much stronger than my painting work.

My painting background continues to influence my photographic work. I’ve always felt comfortable constructing photographic images in similar manner to paintings, playing with camera tilts and shifts and excessive dodging and burning in the darkroom. Likewise, my work remains project-based, although I am constantly romanced by the modernist idea of searching out images in the world.

What advice would you give a budding photographer?

I remember reading a line in the book Art & Fear after I finished my undergraduate studies, and had spent a solid year making absolutely nothing: The work doesn’t make itself. The concept is so obvious, but it really struck a chord with me: the work doesn’t appear unless I do it. If I just make stuff (good or bad), at least I will be making work.

The idea continues to serve me well when I find myself at a crossroad, when life gets overwhelming and demanding and it is hard to find time to make dinner, let alone artwork. I also have learned to trust myself a bit more, knowing that I will always come back to making work, and that a bad day or two (or week or month) doesn’t define my trajectory as an artist.

What served me the best in my formative years, and continues to be so important to me, is the idea that we are all evolving humans, and as long as we are continuing to grow and learn, we are on the right path. Sometimes in the photo (and art) world there is so much pressure to accumulate accolades on a CV. And, sometimes, those accolades aren’t nearly as important as learning, growing, and becoming. We are all evolving, always, and there is a magic and excitement to that process that can’t be represented by lines on a CV.

Has your work been exhibited?

My work has been shown nationally and internationally, including a solo show at the Danforth Art Museum, and group shows at the Rourke Art Museum, The Griffin Museum of Photography, and Wheaton College, among others.

What PRC activities have you participated in?

As an intern some many years ago, I helped with almost everything: gallery sitting, selling tickets at lectures, bartending at openings. I also assisted with research projects and information gathering. Since my time as an intern, I’ve been in regular attendance at PRC events and openings, as well as helping out as a volunteer whenever my crazy schedule allows for it.

How long have you been a member of the PRC?

I’ve been involved with the PRC since 2006, when I started as an intern. In my formative years, I was lucky to have the opportunity to engage in such a prominent institution and see the inner workings of the Center. Over the years I’ve been both a member and a volunteer, and I plan to stay connected ad infinitum.