by Joel Howe

How can you understand the experience of somebody who is losing their mind? It’s an interesting and difficult assignment that Olivia Parker has taken on; her photographic exhibit Vanishing in Plain Sight is on view until April 3, 2019 at Lesley University’s Lunder Arts Center, Porter Square, Cambridge.

The works are from an ongoing project about Parker’s husband John’s terminal struggle with Alzheimer’s Disease. It is not just documentary, but a visual attempt, using empathy and imagination, to understand and express his lived experience as his memory and cognitive ability declined. John died in 2016—the photographs on exhibit were made from 2015 to 2018.

The exhibit pairs photographs (or groupings of photographs) with short explanatory texts that provide additional context. The texts take the form of short anecdotes: for example relating how John struggled to recall the names of friends, or about how he developed a fear of water. They also provide insight into Parker’s artistic thought process while making the photographs, as she struggled to ‘visualize’ John’s experience.

In one particularly poignant image, Tom and Susan, Parker photographed a small elastic-bound bundle of handwritten names on scraps of paper. Parker explains in the text that seeing this made her realize how much John feared forgetting the names of even his closest friends. In this photograph, as well as the other three images of scrawled notes that form a grouping, wispy trails of reflected/refracted light play across the scraps, lending an air of slippery transience to the words.

Themes of fear, loss of control, disorientation, and disintegration are explored throughout the exhibit. In previous work Parker has photographed carefully controlled still-life arrangements in the studio, but here her work becomes more experimental and expressive. Light, movement and abstraction are employed to emotional effect. Changes is an image of nothing but light refracted onto a surface, but the red and white streaks evoke ethereal medical scans: bones and vascular systems.

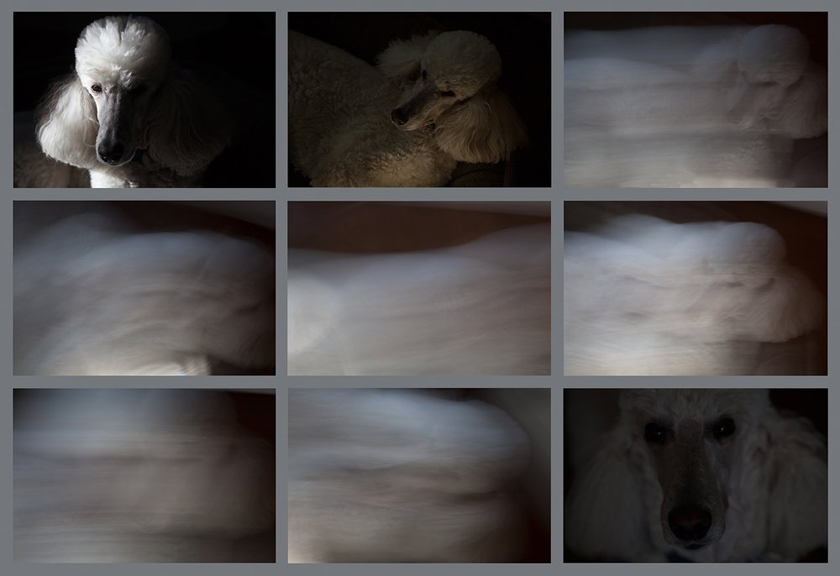

In many of the photographs, the material world starts to disintegrate and become disorienting, expressed through blurring, lack of focus, over/underexposure, or multiple exposure. In Rosie, a grid of nine photos of the family poodle, the dog starts out crisply rendered, but gradually dissolves into a motion-blur of moving white fur. In the abstract triptych Rage, tangled streaks of white and red light are bundled up against a deep black background. Parker explains in the text that as the disease progressed, John would sometimes have fits of rage that spun out of control.

In other images, Parker literally tries to visualize what she imagines the world might look like, through John’s eyes and brain. Darkness Brings, a triptych of dark blurred rectangles against a bright white backdrop, illustrates the increased sensitivity to light and dark that he experienced, especially with windows, resulting in a desire to close all the window shades during the day. With the motion-blurred black line and bright colors of City, Parker speculates how the city of Boston might look to John, as they drove through it on the way to medical appointments.

Some photos in the exhibit employed a more intellectual approach that I found to be generally less engaging. But overall, Parker’s experimental method has produced an evocative and emotionally-visceral exhibition. Dealing with such an intimate and difficult subject matter as Alzheimer’s Disease, the overall tone is one of uneasiness and disorientation, but the show also contains welcome respites of calm and acceptance. One image that sticks with me is a refracted swirl of light—ghostly white trails and a red form like a heart, playing across a scrap of paper with a single word scrawled on it: BE.

Headline image: ‘Be,’ 2016 © Olivia Parker

Joel Howe is an architectural and fine-art photographer based in Cambridge, MA. He also edits and maintains the Call for Entries feature of the PRC website.