On view at Addison Gallery of American Art (Andover, MA) until 03/03/19. Featured image: Roger Minick’s “Woman with Scarf at Inspiration Point, Yosemite National Park, California” from Sightseer Series, 1980.

By Joel Howe

Local photography teachers would be well-advised to arrange a class field trip over to the Addison Gallery in Andover to catch the current exhibition: “Contemplating the View: American Landscape Photographs”.

Drawing deep from the Addison Gallery’s stellar permanent collection, the exhibit presents a thoughtful overview of the history and trends of American landscape photography, as well as its more contemporary manifestations. Spanning four rooms, the exhibit starts out with a largely chronological presentation, and develops into more thematic groupings.

First Room: Earliest Work

The earliest work is simply astounding. Pioneers such as Eadward Muybridge, Carlton Watkins, and William Henry Jackson represent here the unbridled enthusiasm for exploration and documentation of the vast Western landscape, starting in the 1860s and ’70s. Well before Ansel Adams’ time, Yosemite Valley is already showing up as the quintessential landscape subject in “Mammoth Plate” albumen prints by Muybridge and Watkins.

While these early prints evoke a sense of the sublime awe that must have been felt by early explorers unaccustomed to the vast scale of the Western landscape, they also provide some early glimmers of the ecological devastation that later landscape photographers addressed in earnest. Watkins’ images of gravel-mining operations, and the construction debris in Jackson’s railroad photos, hint at the darker side of the Westward expansion.

These Mammoth Plate prints also represent incredible technical feats—they were created by using huge view-cameras that produced glass plate negatives up to 18”x22”, which were then contact-printed onto albumen paper. These enormous glass-plate negatives had to be hand-coated with light-sensitive emulsion in the dark, quickly exposed in the camera, and then developed in the dark again, all while the emulsion was still wet. This required the photographer to haul a portable darkroom tent, in addition to the massive camera, tripod, and sheets of fragile glass. Despite these logistical challenges, the prints themselves are near perfect—massive, yet with no visible grain and virtually unlimited detail.

While Yosemite may be the ultimate American landscape subject, I was pleased to see that the Addison has also included several very early works by more local photographers. Examples are an 1858 salt-print of Mt. Washington by Franklin White, and an albumen print from the 1880s by Charles Hibbard of “The Flume,” a popular White Mountains destination.

Second Room: Early 20th Century

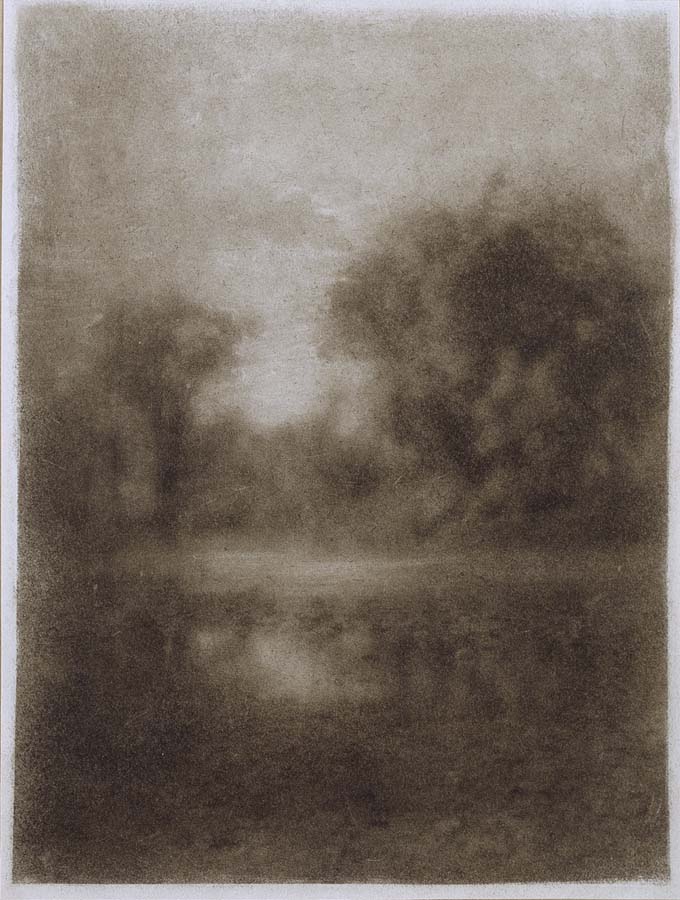

The second room of the exhibition illustrates how, in the early 20th century, photographers started to become interested in the possibilities of the medium as “Fine Art”, rather than just documentation. Work from this period became more emotive—softer-focus, more painterly—and acquired the moniker “Pictorialism.” Landscape photographs were often taken intentionally out of focus, or using special “soft-focus” lenses, and printed on hand-coated textured paper, using gum-printing, or platinum-printing to give a painterly or hand-drawn look. One 1919 photograph by George and Hebe Hollister, “Elms by the River,” is so impressionistic that I would have sworn it was a charcoal drawing.

The room also shows work by Alfred Steiglitz, who started his career in the Pictorialist tradition before realizing that emulating painting didn’t take advantage of photography’s innate strength, which is crisp realism. Stieglitz helped direct the medium back towards “straight photography.” The exhibit includes like-minded photographers such as Edward Weston, who belonged to the f64 Group—so-called because of its advocacy for using the smallest camera-lens aperture, f64, which resulted in maximum sharpness of focus.

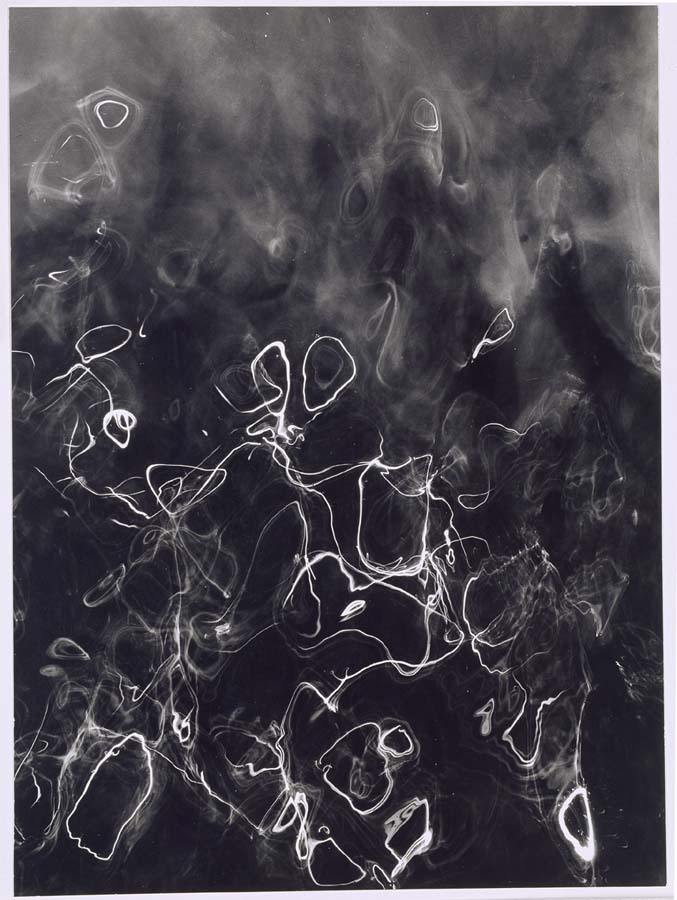

Just as the Pictorialist photographers were influenced by the impressionist painters of the era, in the 1940s and ’50s, abstract expressionism influenced photographers such as Harry Callahan and Minor White, who began to explore the possibilities of abstraction in landscape photography. Callahan’s “Sunlight on Water” from 1943 is a standout example from this period.

In the 1960s and ’70s, some photographers began to re-evaluate our relationship to the landscape. Rather than idealizing the view, they opted for a more realistic representation of the typical American experience landscape. Robert Frank includes the less romantic side of the Western landscape in his 1955 “Santa Fe (Gas Station)” and Robert Adams includes tract-home subdivisions in the foreground of his mountain landscapes. Adams was a founding member of the “New Topographics” school of landscape photography, where man-made features are intentionally included in the view.

Of course, there’s another well-known photographer named Adams, and Ansel is represented in this room as well, with several photographs made in Yosemite and the Sierra Nevadas. I found it interesting that while Ansel Adams may be one of the first photographers to come to mind when thinking of “American Landscape Photography,” his photographs seemed out of step with the historical movements of the medium. His work expresses an innocent awe of the landscape, but was made far later than those early pioneers. It is emotional and expressive, but crisply focused and not connected to the Pictorial movement. The work is contemporaneous with the New Topographers, but he refuses to allow the man-made into his viewfinder. Ansel Adams seems off on his own track, successful and influential, but also disconnected from the cultural conversation about the meaning of landscape photography.

Room Three: The 1970s and ’80s

The third room of the exhibit follows landscape photographers of the 1970s and ’80s, veering into conceptual and postmodern territory. The photographer becomes no longer an objective documentarian, but rather an active participant in the landscape, and self-reflective about the act of photographing itself.

For example, rather than photographing Mt. Rushmore directly, Lee Friedlander chose to photograph the reflection of the mountain in the gift-shop window, commenting on how we “consume” the landscape. The 1980 image (the feature image of this post) by Roger Minick depicts a grand view of Yosemite Valley, but with a woman in the foreground wearing a gift-shop head scarf imprinted with the exact same view. With his “Altered Landscapes” series, John Pfahl intervenes directly in the landscape, placing objects into the scene and playing perceptual tricks based on perspective.

Room Four: Contemporary Work

The final room of the exhibit covers more contemporary work and suggests the many different directions of current photography. Several of the themes that emerged earlier in the exhibition are re-examined here.

The environmental destruction first suggested by Watkins is further explored in Joel Sternfeld’s images of suburban homes on the edge of a sinkhole, or Katherine Wolkoff’s documentation of the destruction wrought by Hurricane Katrina.

Considerations of “man-made” versus “natural” landscapes and ideas about beauty that were first explored by the New Topographics photographers are further investigated in Lewis Baltz’s “Candlestick Point.” It is a wall-covering installation of 8”x10” prints of overgrown parking lots and trash-strewn urban edge-conditions.

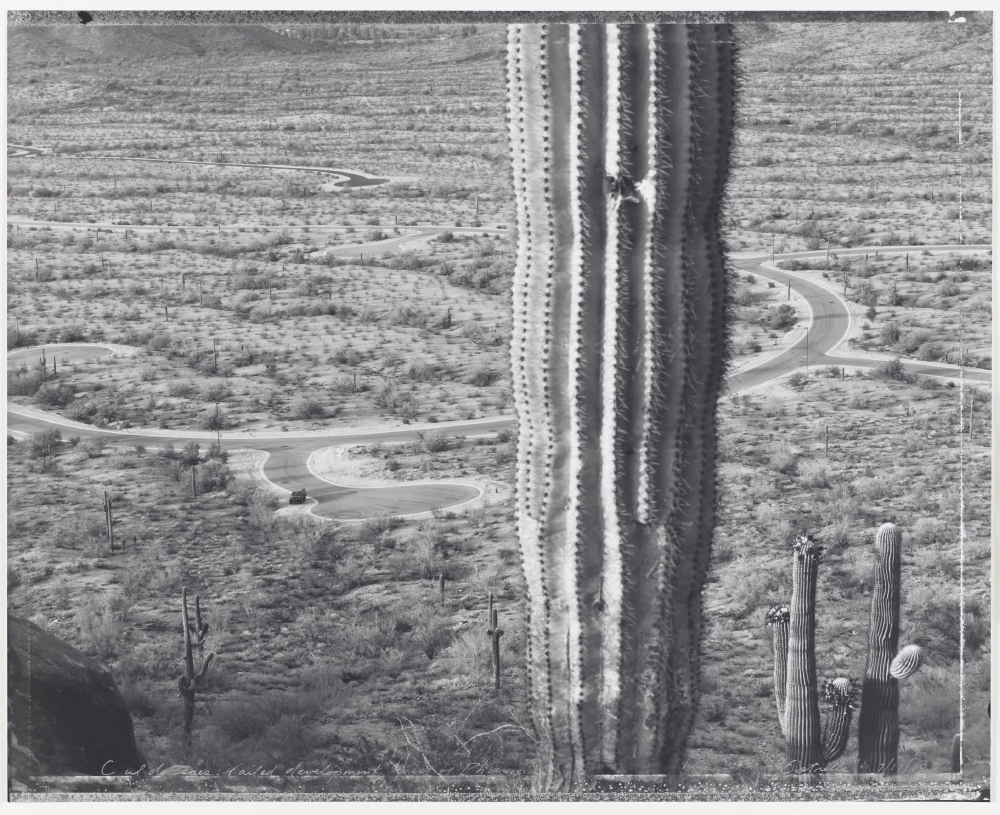

In his 1990 “Cul de Sac: Failed Development West of Phoenix,” Mark Klett builds upon the earlier work of Robert Adams with his image of suburban development gone awry.

Concerns raised by the postmodern movement, about oppression, racism, and under-represented minority perspectives, are further examined in works by John Willis documenting Native American gravesites, and Debbie Kaffery’s images of New Orleans neighborhoods still languishing a year after Hurricane Katrina hit.

This final room of the exhibit, with its multitude of different photographic approaches, suggests a fracturing in the linear narrative of the history of landscape photography. Are the images of death and destruction (gravesites, battlefields, hurricanes, burning houses) meant to suggest a collapse in the traditions of American landscape photography, hastened along by the ubiquity of smart-phone photography posted to Instagram? One photograph near the end of the exhibit seemed to embody the current state of affairs: Matthew Pillsbury’s 2006 “Cell Phone on Venice Beach,” a ten-minute long exposure of the ocean at dusk, with the glow of a cell phone glimmering like a ship’s navigation lights upon the horizon.

Have we all turned inward, captivated by our little devices, or can we still connect with the sublime, with the vast ocean and sky in the gloaming? Offering hope for the latter, an adjacent photo by Barbara Bosworth, “Fireflies in a Jar, Mentor, Ohio” (1995), is a beautiful image of natural wonder and beauty close at hand.

Joel Howe is an architectural and fine-art photographer based in Cambridge, MA. He also edits and maintains the Call for Entries feature of the PRC website.