Mark Feeney for the Boston Globe

August 10, 2022

“Exposure 2022,” the 26th iteration of the Photographic Resource Center’s annual juried show, drew nearly 200

entries. The juror, Chicago gallery owner Catherine Edelman, selected the work of 12 photographers. Their work is impressively diverse. Yet shared within that diversity is an often-inventive relationship to the medium and its own relationship to other media. If that sounds overly conceptual, it’s not. The visual appeal of so many of the images on display makes sure of that. The exhibition runs at the fort point Arts community Gallery, in the Seaport, through Sept. 15.

Ultrachrome inkjet print

There are three examples where photography is most straightforwardly in conversation with another medium. Fritz Goeckner’s three self-portraits look almost indistinguishable from pastels. April Friges’s pair of collaged arrangements of colored photographic paper have a dimensionality that gives them a sculptural quality. The way they curl up is like a declaration of independence from photographic flatness. Pamela Hawkes, who lives in Rockport, has a quartet of visually lavish flower arrangements, derived from paintings, which harken back to the European still life tradition that ran from the 17th century and well into the 19th. Bryan Florentin alludes to the still life tradition, and trompe l’oeil, too, with his “prepared Shelves.” There are four on display. The procedure could hardly be simpler. florentin takes various objects and puts them on metal shelving and then photographs the arrangement. The images are big, nearly 3-feet square, and shown unmatted. The presence of x-shaped metal struts in front of the shelves and brick walls in back of them creates a sense of visual layers, giving the photographs a sense of dimensionality cunningly at odds with their ostensible spareness.

Melanie Walker, one of two photographers in “Exposure” whose work is in black and white, has a different relationship to dimensionality and layering. Here the layering is temporal and also familial. She’s taken decades-old negatives made by her father, laminating past and present. “I am interested in the physicality and material qualities of the disrupted surfaces and how they interact with the images recorded so long ago,” she writes. The other photographer with work in black and white is Julie Mihaly. There are four. Taken during pandemic isolation, they deal in a different sort of layering, one of the most profound: the superimposition of the man-made world on the natural. “Tattered Billboard with face,” for example, has that namesake visage framed by that namesake sign, with a half-dozen and more trees behind, and beyond them fences, a portion of house, a couple of pickup trucks.

archival inkjet print

The four photographs from Sue Palmer Stone’s series “Embodiment — Salvaging a Self ” have a twofold relationship to other media. What we see are assemblages of discarded materials. Yet Stone suppresses a sense of depth and solidity, photographing them so that they resemble abstract paintings of great elegance and simplicity. Being drawn to the discarded is something Stone shares with Joni Lohr, who lives in Jamaica plain. “Abandoned places ask questions,” she writes. Not so foolish as to try to answer those questions, Lohr takes photographs that amplify them. A title like “The Last Rocking chair” is emblematic of her work. What it can’t convey, though, is the rich, transfixing color of her images. It’s not just objects and places that are discarded. people can be, too, discarded or dismissed. Judyta Grudzien helps support herself by working as a housekeeper. for her extraordinary series “We Love You,” she attached unexposed color film to the rubber gloves she would use while cleaning. The distressed film she would then use to take photographs. The resultant images are striking in appearance, quite beautiful, in fact, and that much more powerful when looked at with an awareness of what was involved in producing them.

David Sokosh’s “Things That Look Like the MOON (but are not the moon)” is elegant and charming — alluring even. It doesn’t just relate to another medium. It be longs to one. “Things” is an artist’s book, displayed in the show opened up, accordion style. It consists of 16 cyanotype images of common objects — soccer and tennis balls, a cantaloupe— that look, yes, lunar. Accompanying each image is an amusing extended caption. Cyanotype is a 19th-century photographic process in which a positive emerges as blue. Architectural blueprints are cyanotypes. So if Sokosh’s book had a theme song it would be Rodgers and Hart’s “Blue moon.” If Mccormick Brubaker’s four studies of what he rightly calls “the emotion of the color blue” had a theme song, it might be “How Blue can You Get.” They show nothing more exalted than the facade and parking lot of a public restroom at the cape cod National Seashore. But the way Brubaker handles light and color is exalted. Two of the four are nocturnes (speaking of other media – more music), and the handling there is nothing short of sumptuous.

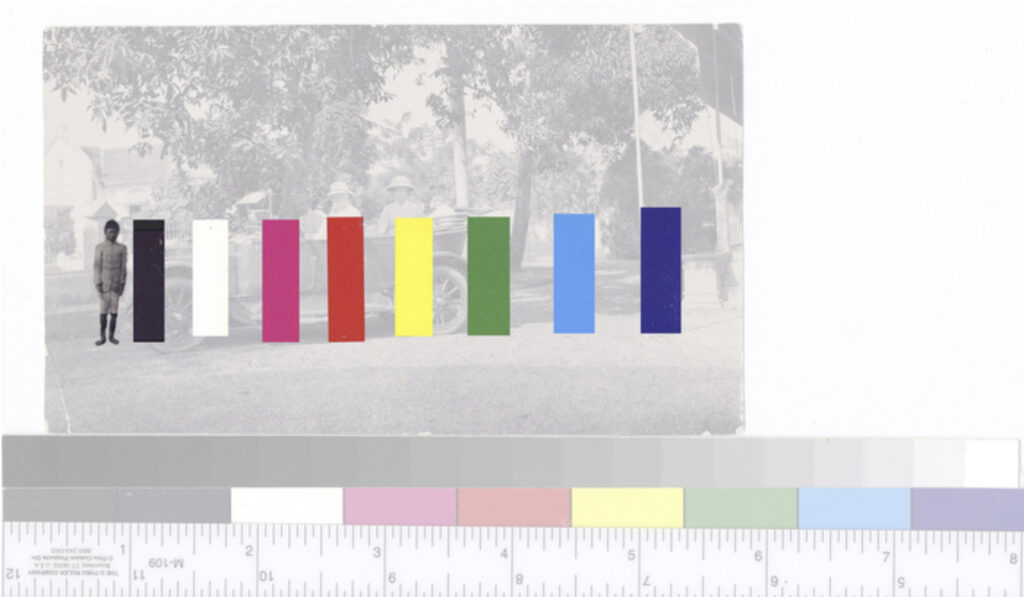

2022 photocollage, acrylic

The PRR gives awards to three “Exposure” photographers. This year first prize went to Jason Reblando, the other two to Lohr and Stone. A Boston college graduate, Reblando is of filipino descent. The three images from his series “Field Notes” combine archival photographs from the period when the United States colonized the Philippines with Reblando’s reworkings of those images, adding contemporary elements, such as color bars or, in the case of “Filipino Boy in front of Admiral Dewey’s car,” a ruler. That word has a double meaning in this context, with social and political layerings added to the visual and temporal layering found in other “Exposure” photographs. The presence of the ruler also recalls a famous 1872 photograph by Timothy H. O’Sullivan. The artistic medium that Reblando’s image is in conversation with is photography itself.