essay

Land/Mark:

Land/Mark:

Locative Media and Photography

by Leslie K. Brown, PRC Curator

Published in in the loupe (March/April 2005, Volume 29, Number 2)

Anyone who knows me realizes that I am terrible at directions. I have also been known, via some sort of weird magnetic ability, to destroy computers and other technological devices. Perhaps for these reasons, mapping, instruments, and the theories that surround them have long interested me. Uniting geography, media, and photography actually has a long history and thus a befitting topic for a festival celebrating art and technology. Longitude, draped in tales of sea adventures and socio-political aims, is a product of our modern world; standard time, an important factor in calculating where you are, was only instituted in 1883 as system for maintaining railroad timetables. Photography famously entered into these histories through the four “Great Surveys” of the United States Geographical Survey of the late 19 th century. Landscape photographers such as Timothy O’Sullivan accompanied scientists under the auspices of the War Department and the Department of the Interior (under which the same Geological Survey oversees GIS and Landsat photos today) across parallels and meridians into the West. Even with all of this cultural baggage swirling in my head, or perhaps because of it, I still manage to get lost.

Using the parsed phrase “Land/Mark” and locative media and geographical systems as a starting point, this group show features work by Margot Kelley, Brooke Knight, Josh Winer, and the new media, global public art project Yellow Arrow (yellowarrow.net), but also points to various other exhibition and events related to mapping all over the city. Held in conjunction with the Boston Cyberarts Festival (April 22-May 8), this gallery showing represents the third time the PRC has joined local organizations since the festival’s founding in 1999. Owing to publication schedules, I am struck by the fact that most people will read this essay before the actual art is even installed. This irony—an exhibition that at first glance is about place and specificity—actually serves to elucidate a very important point. That is, although you could visit the places pictured in the photographs on display, that meeting and interaction is subjective, changing, and always new. The artists too use the devices and systems in ways contrary and sometimes at odds with their invention. The big brother all-seeing modernist “eye” and theories related to the panopticon and surveillance, represented here by satellites and cell towers, are offered up for discussion at every angle.

Recently, there has been an explosion in the artworld addressing the idea of mapping—expanding, personalizing, obfuscating, and even undermining cartographic impulses and ideas. Critics have taught us that maps are social constructions and can be a way of inscribing authority onto the land. New art forms, with a nod to Fluxus, Situationists, performance art, and the French flâneur, encounter and perform urban areas in a blending of psychology and geography dubbed psychogeography. Simultaneously, regular folks inspired by the democratic and relatively free (in principle) nature of locative media, adapt and use these tools for recreational uses that sometimes verge on the artistic. The Degree Confluence Project (confluence.org) for example, seeks to visit “each of the latitude and longitude integer degree intersections in the world, and to take pictures at each location.” For them, the act of getting there is enough, and with all corners of the earth seemingly accounted for, they delight in “discovering” new places sometimes literally in a backyard. Another project (geosnapper.com) encourages amateur photographers to capture a beautiful scene and post the coordinates online so others can re-visit (and possibly re-take and re-experience) their photograph.

A map cannot begin to convey the overwhelming sum of its parts. The artists here address the idea of interfacing with technology and larger networks to determine or showcase location, but they also remind us about another important factor in the equation, the individual, and by extension community. Humans constantly alter their environment, and no landscape is neutral. The photograph serves as evidence of “having-been-there” but also serves as a mark, a small effort, but almost universal and innate urge, on the part of a human being to capture, command, alter, show, and share. Another theme that also emerges in this exhibition is that of gaming. (A modern-day merging of art with orienteering, scavenger hunts, and road rallies?) In both geocaching and Yellow Arrow, citizens become modern-day explorers ferreting out treasures and new experiences. Most notably, all of the works insert the human element, positively and negatively, back into the landscape and back into the technology. These artists participate in some form of marking the land while showing the marks already on it.

Of all of these, GIS is perhaps the most umbrella of the terms, a geographic information system which at its most general level is a computer system designed to manage location data.

GPS , or global positioning system, was originally developed by the US Department of Defense. It consists of a constellation of at least 24 earth-orbiting satellites (with 3 extras) with atomic clocks. The receiver needs at least 4 satellites locked in to determine its position and through a fairly simple mathematical calculation know as trilateration. From this, GPS can determine your approximate location, give or take 6-20 feet, in terms of latitude, longitude, and altitude. Interestingly, the handheld GPS device actually uses its own inaccuracy to determine where you are. On May 1, 2000, Bill Clinton announced that "Selective Availability" (a sort of scrambling of signals to consumers) would be turned off, allowing GPS to be even more accurate.

SMS , or short messaging service, was originally designed for use with GSM ( Global System for Mobile Communications). Akin to Wifi (wireless fidelity), cell phones are basically radios. The cellular system links the city through towers by creating “cells,” usually about 10 miles wide. When thought of in this way, such technology is territorial (roaming in and out of range) and functions by constantly locating where you are.

The Landsat program is the oldest system for acquiring earth imagery from space. The current satellite Landsat 7 has been in orbit since 1999 and can collect and transmit over 500 images per day. Although managed by NASA, its data is collected and distributed by the US Geological Survey.

As Kelley explains in the book’s preface, “Because geocaches are designated by latitude and longitude, hunting for them involves the curious experience of simultaneously knowing exactly where you are going but having no idea where it ‘really’ is or what it will look like until you finally arrive. While that experience was common for explorers in earlier eras, it has become a rarer and rarer experience in our media-saturated world.” When photographing, Kelley underscores this, thus you actually will never see any caches in her photographs, but the sentiment, a detail, a moment, that perhaps this person (known only by a username) wanted to share with the world. Among the locations/photographs are a dock near Alfred Stieglitz’s home in Lake George, the underpass to a popular Boston subway T-stop, and even a cache on a classified government site in the Arizona dessert. In her poetic descriptions that accompany each photograph, Kelley touches on everything from natural history to philosophy in guiding us visually in how people, seen and unseen, mark the land.

Kelley has a diverse background that includes a Ph.D. in American Literature from Indiana University and a MFA in photography from MassArt. She currently teaches literature at Bentley College. As a part of the Nature & Inquiry artist group related to MassArt’s SIM (Studio for Interrelated Media) program, she collaborated on the award-winning artwork “Invisible Ideas,” a GPS-enabled Artwalk through the Boston Public Gardens and Common for the Copley Society of Art held during the 2003 Boston Cyberarts Festival.

CAPTION: Margot Kelley, N 42 ° 21.459 W 71 ° 04.225 , 2002, C-print mounted on aluminum, 16 x 20 inches, Courtesy of the artist

In his series Landmarks, Knight traveled to well-known New York City cultural and civic attractions. Instead of looking up, the way most visitors do when ingesting culturally dictated spaces or become lost, he looked down and photographed the sidewalks. The coordinates of where foot meets pavement—an oft-overlooked interface—were later notated and then overlaid over the scene. To these tools, all locations are just a collection of numbers and thus, via a sort of democratic leveling, the Empire State Building becomes the same as Times Square. Cracks in the sidewalk, the elevation of a step, and the grain of granite seem both alien and monumental. Likely, his act of photographing was quite humorous to passers-by, a bizarre twist on the tourist photograph (“I was literally standing here”). Hung in a 2-column grid, 4 frames high, the shape of the final display even alludes to the height of buildings and the shape of Manhattan. Knight’s other work “Every Environment is Text Rich #2” was completed simultaneously with Landmarks. Using a digital video camera at the same locations, he spelled out title phrase by moving the camera in the shape of each letter. In new series created for this exhibition, he will select minute intersections of latitude and longitude, and make rubbings of the ground—literally and metaphorically “traces”—combining them with photographs of the sky above.

In his series Landmarks, Knight traveled to well-known New York City cultural and civic attractions. Instead of looking up, the way most visitors do when ingesting culturally dictated spaces or become lost, he looked down and photographed the sidewalks. The coordinates of where foot meets pavement—an oft-overlooked interface—were later notated and then overlaid over the scene. To these tools, all locations are just a collection of numbers and thus, via a sort of democratic leveling, the Empire State Building becomes the same as Times Square. Cracks in the sidewalk, the elevation of a step, and the grain of granite seem both alien and monumental. Likely, his act of photographing was quite humorous to passers-by, a bizarre twist on the tourist photograph (“I was literally standing here”). Hung in a 2-column grid, 4 frames high, the shape of the final display even alludes to the height of buildings and the shape of Manhattan. Knight’s other work “Every Environment is Text Rich #2” was completed simultaneously with Landmarks. Using a digital video camera at the same locations, he spelled out title phrase by moving the camera in the shape of each letter. In new series created for this exhibition, he will select minute intersections of latitude and longitude, and make rubbings of the ground—literally and metaphorically “traces”—combining them with photographs of the sky above. Knight’s background in literature combined with a long-standing interest in semiotics has led to his current work with words and images. His art often deals with writing, and involves the act of inscribing onto a variety of substrates. Almost all of his pieces address technology and most interface with the internet, with some existing only in that space. (See more online at brookeknight.com.) Knight received his MFA in photography from California Institute of Arts and is currently an Assistant Professor of New Media at Emerson College. Regionally, he has shown at Art Interactive in Cambridge, ArtSpace in New Haven, and University of Maine.

CAPTION: Brooke Knight, Landmarks series, Empire State Building, 1999, Ink jet print, 11 x 14 inches, Courtesy of the artist

Josh Winer

Winer’s work is a part of an ongoing series depicting landscapes in flux. Using a view camera in the tradition of 19 th century Western photographers, Winer travels to scenes of earth as raw material or by-product: a Quincy quarry filled in with excess dirt from the Big Dig, a gravel pit in Vermont, and a stockpile of road salt under a bridge in Chelsea. While the photographers of the US geological surveys documented for the purposes of expansion, namely the railroad, Winer’s work addresses in part New England’s penchant for reclamation, transformation, and the automobile. Here the land is a discursive space, Winer claims, and "Through these very acts of excavating the earth and creating new landscapes, the earth itself becomes an agent of our ambitions and desires."

Winer’s work is a part of an ongoing series depicting landscapes in flux. Using a view camera in the tradition of 19 th century Western photographers, Winer travels to scenes of earth as raw material or by-product: a Quincy quarry filled in with excess dirt from the Big Dig, a gravel pit in Vermont, and a stockpile of road salt under a bridge in Chelsea. While the photographers of the US geological surveys documented for the purposes of expansion, namely the railroad, Winer’s work addresses in part New England’s penchant for reclamation, transformation, and the automobile. Here the land is a discursive space, Winer claims, and "Through these very acts of excavating the earth and creating new landscapes, the earth itself becomes an agent of our ambitions and desires."

The only notion of specificity comes via Winer’s choice of titling his compositions using their GPS coordinates. This point of entry, however, is paradoxical, and ultimately invites and releases viewers. We could return to the vicinity, but similar to the Greek philosopher’s adage that "one can never step into the same river twice," once recorded, these landscapes have indelibly changed. These piles are building blocks and leftovers from other sites, destined to move and be torn down at will. One is struck by the lunar quality of many of the scenes (an imprint from a construction vehicle might be likened to a moon rover) and consider how minimal can a landscape actually be? Viewers are plunged into the picture plane with little or no indication of the place—the periphery becomes the focus—and we apprehend the place-in-itself. Although initially alluding to the hand of man and commercial and political ambitions, agency sometimes seems transferred to the earth. Sand and rocks fall, and ultimately, gravity and entropy take over. Thus we witness the land being marked, and also marking itself.

Winer received his MFA in photography from Massachusetts College of Art in 2004. He has served as the media stockroom manager at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston and the Boston Photo Collaborative. Recently, he accepted a position as Lab Manager and Adjunct Faculty at the Art Institute of Boston. His first solo show was at Clifford•Smith Gallery in October 2004.

CAPTION: Josh Winer, 42° 57’ 11N, 073° 12’ 24W, 2004, C-print, 40 x 50 inches, Courtesy of the artist and Clifford•Smith Gallery

Yellow Arrow

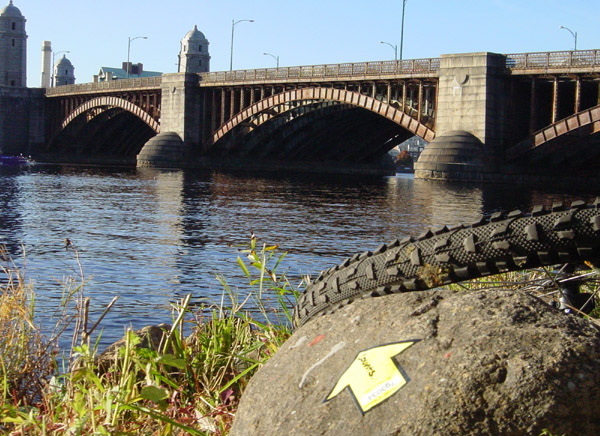

As stated on their website, yellowarrow.net, Yellow Arrow merges "sticker culture with wireless media, creating an interactive forum for people to leave and discover messages pointing out what counts in their environment." Participants place arrows drawing attention to locations and sites of their choosing, and are invited to post photographs to their website. Each arrow has a unique code, and by sending a text-message (SMS) from a mobile phone to a number a short message becomes attached to a site. If someone encounters an arrow when ambling about, he or she can send the code to the number and immediately receive the point associated with it. Cities from Berlin to Zürich to San Francisco are included in their database, with new additions added daily. Through this location-based exchange, the group asserts, "the Yellow Arrow becomes a symbol for the unique characteristics, personal histories, and hidden secrets that live within our everyday spaces."

As stated on their website, yellowarrow.net, Yellow Arrow merges "sticker culture with wireless media, creating an interactive forum for people to leave and discover messages pointing out what counts in their environment." Participants place arrows drawing attention to locations and sites of their choosing, and are invited to post photographs to their website. Each arrow has a unique code, and by sending a text-message (SMS) from a mobile phone to a number a short message becomes attached to a site. If someone encounters an arrow when ambling about, he or she can send the code to the number and immediately receive the point associated with it. Cities from Berlin to Zürich to San Francisco are included in their database, with new additions added daily. Through this location-based exchange, the group asserts, "the Yellow Arrow becomes a symbol for the unique characteristics, personal histories, and hidden secrets that live within our everyday spaces."

Remarkably, after learning about Yellow Arrow, I began to notice them everywhere: on the BU Bridge (text = "Perspective helps us see the way. We choose bicycles to discover every angle in our urban playground"), and in a classroom at the Art Institute of Boston. On display at the PRC will be a live-feed slideshow from their online photographic database, which during the Cyberarts Festival will showcase only Boston area arrows. In a city known for its established landmarks, this project puts the control in the hands of the people who know it well. New landmarks will be created and the city activated in a recipe that is one part subjective mapping, one part annotated environment. In essence, Yellow Arrow allows Boston to curate itself and every person to be a part of an artistic act.

Yellow Arrow first emerged during the 2 nd PsyGeoConflux conference in May 2004, launched completely in the Fall, and most recently participated in Art Basel in Miami. Yellow Arrow has been featured in Wired Magazine, Metropolis, Mass Appeal, TimeOut NY, and countless international publication publications including Le Figaro, Liberation in France, RAI in Italy and Diari de Barcelona in Spain. Yellow Arrow is a project initiated by Counts Media, a mobile art, entertainment and theatre company based in New York City. (For more information visit www.countsmedia.com.) Their combined background includes photography, experimental live performance, urban exploration, computer programming and location-based storytelling.

CAPTION: Yellow Arrow #g3034 by "newurban." "Oh, if only I had the words of the poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. But sometimes, you just don't need to say a thing." Courtesy of "newurban" and yellowarrow.net

Conclusions

Clearly, something new is happening—these artworks here stretch the boundaries of what is known as the photographic and geographic—and territories need to be redefined, if not leveled. (Interestingly, both of terms, photographic and geographic, reference mark making—literallymeaning light and earth writing.) Remarking on new technologies begetting new maps in You are Here: Personal Geographies and Other Maps of the Imagination, writer Stephen S. Hall offers that new delineations “lend themselves to a form of bushwhacking that is more interior, philosophic, imaginative.”kanarinka, one of the founders of a local art collective of a psychogeographical bent, likewise ponders, “Cartographers used to make maps. Artists used to make pictures. What do we do now?…”

The hunting origin of the photographic term “snapshot” helps in navigating this topic. This urge underlies this exhibition and is an apt coda for this essay. Guided by an internal compass and armed with unexposed film, this connotation serves us well in thinking about the changed topography (physically, politically, and culturally) that we now inhabit and our urge to locate and capture it photographically. I leave you then where we began: lost, but hopefully liberated. A quotation, then, to conclude: the “Bellman’s Speech” from Lewis Carroll’s Hunting of the Snark (1876), in which a group of adventurers search for a legendary, fictional, beast using a plain sheet of paper:

He had bought a large map representing the sea,

Without the least vestige of land:

And the crew were much pleased when they found it to be

A map they could all understand.

"What's the good of Mercator's North Poles and Equators,

Tropics, Zones, and Meridian Lines?"

So the Bellman would cry: and the crew would reply

"They are merely conventional signs!

"Other maps are such shapes, with their islands and capes!

But we've got our brave Captain to thank"

(So the crew would protest) "that he's bought us the best--

A perfect and absolute blank!"

Selected Bibliography

Harmon, Katherine. You are Here: Personal Geographies and Other Maps of the Imagination. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2004.

kanarinka, “Maps and Ovens: An Incomplete Dictionary of Mapping Practices,” Cartographic Perspectives, Special edition: “Maps and Art” edited by Denis Wood, publication forthcoming.

Kelley, Margot Anne. Local Treasures: Geocaching Across America, Stauton, VA: Center for American Places, publication forthcoming (October 2005, ant.).

Solnit, Rebecca. Wanderlust: A History of Walking. New York: Penguin Books, 2000.

Glowlab, www.glowlab.com, the hub of psychogeographic practices and sponsor of Psy.Geo.Conflux conferences. Note that the next conference will be held in Providence, in Mid May. Visit provflux.blogs.com for more info.![]() Copyright © 2002, Photographic Resource Center, Inc.

Copyright © 2002, Photographic Resource Center, Inc.