In particular, any idea that old technologies can tell us anything about

new ones has been discouraged by two futurological tropes (supported in

varying degrees by critical theory). The first is the notion of supersession

- the idea that each new technological type vanquishes or subsumes its

predecessors: "This will kill that," in

the words of Victor Hugo's archdeacon that echo through debates about the

book and information technology. The second is the claim of liberation,

the argument or assumption that the pursuit of new information technologies

is simultaneously a righteous pursuit of liberty. Liberationists hold,

as another much-quoted aphorism has it, that "information wants to be free"

and that new technology is going to free it. The book, by contrast, appears

never to have shaken off its restrictive medieval chains.

In particular, any idea that old technologies can tell us anything about

new ones has been discouraged by two futurological tropes (supported in

varying degrees by critical theory). The first is the notion of supersession

- the idea that each new technological type vanquishes or subsumes its

predecessors: "This will kill that," in

the words of Victor Hugo's archdeacon that echo through debates about the

book and information technology. The second is the claim of liberation,

the argument or assumption that the pursuit of new information technologies

is simultaneously a righteous pursuit of liberty. Liberationists hold,

as another much-quoted aphorism has it, that "information wants to be free"

and that new technology is going to free it. The book, by contrast, appears

never to have shaken off its restrictive medieval chains.

Together, ideas of supersession and liberation present a plausibly united front. But this front, I want to suggest, conceals some significant conflicts. First, cultural arguments for supersession lean heavily on the language of postmodernism, while liberationists' arguments about emancipation are laden with ideas of postmodernism's great antipathy, "the enlightenment project." And second, technological ideas of supersession understandably expect progress through technology, while liberation looks for freedom from it.

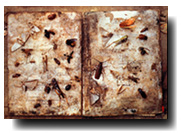

Along one stretch of wall I found a bookcase, still miraculously erect, having come through the fire I cannot say how [...]. At times I found pages where whole sentences were legible; more often, intact bindings, protected by what had once been metal studs [...]. Ghosts of books, apparently intact on the outside but consumed within.